A few months ago, I had the privilege of interviewing my own high school violin teacher, my aunt Valerie Sullivan, on this topic.

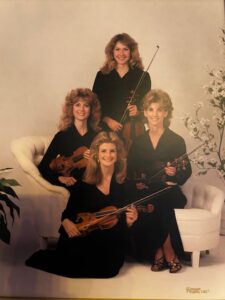

Over the course of her career, Valerie has served as a violin professor, strings sectionals coach for the youth symphony, orchestral musician, soloist, chamber musician, and private violin teacher. She has helped dozens of students prepare for chair auditions, college auditions, juries, and concerto competitions.

Interview:

Valerie, how did you start the violin?

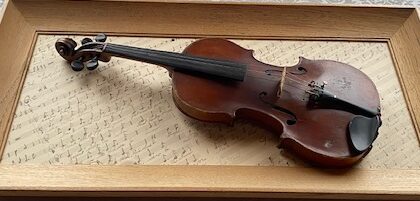

It’s interesting because I’m part of a large family, the oldest of ten. I started piano when I was about five. Because we had an old violin from one of my dad’s relatives, a country violinist, my parents wanted me to learn. I was pretty cooperative, so I agreed. Afterwards, I taught several of my siblings to play, including your mother.

Can you tell us about your involvement as a coach for the Youth Symphony?

It’s a wonderful program that has evolved over time. I’ve been the first violin section coach for over forty years. Growing up, I participated in the Youth Symphony program, as well as my husband, who played French horn. At that time, we didn’t have coaches. I was on the ground floor when they began the coaching program, which has been a wonderful addition. Now we have a first violin coach, second violin coach, viola coach, cello coach, winds coach, brass coach, etc. We coaches help with the details of the instrument because we play it ourselves.

We reserve one hour out of the three-hour rehearsal for coaching. I give them fingerings, bowings, discuss style, and work on the really hard passages many of them can’t figure out on their own. I also think it’s important that our private students have group playing experience. They learn things like tremolo that they don’t need for most solo literature.

What was it like to teach a collegiate studio in addition to your private studio?

It was a tricky balance. I felt a tremendous responsibility to both my private students and the collegiate students. The latter theoretically would be at a more advanced level. I needed to make them ready to face the music world. I was also able to recruit several of my private students to the college if they were a good fit.

In my studio, I want everyone to do their very best and reach the highest level possible, taking into consideration every student’s different circumstances. With my advanced students, I offer a lot of additional lessons and extra time, for those who are interested. Frequently there isn’t enough time in a one-hour lesson to do everything we want to accomplish. We often need two lessons a week in order to work on technique, like études and scales, as well as Bach. Then in the next lesson we tackle more technique and focus on another piece, like a concerto or sonata. This system works really well. By breaking the lessons into two sessions, the students learn much more quickly.

You specialize in working with advanced students. How do you prepare them for college auditions and concerto competitions?

Again, it takes a lot more time to make sure these students are fully prepared. Some auditions are more strenuous than others. I’ll often play their part on the piano to reinforce ear training and good pitch. Next, I record students in order for them to hear how they sound. They say things like, “I didn’t know I was doing that,” “I didn’t know I was rushing” or “I was out of tune.”

The next step in the process involves mock auditions and practice recitals, especially for concerto competitions. Most of my students perform 6-8 times with their piano accompanist in different venues to prepare for the final audition. This helps them to see their strengths and weaknesses so that they can work on these areas in advance. As a result, the competition itself is not so nerve-racking because they’ve been performing the piece for so long. You have to practice nerves in addition to notes.

How do you prepare yourself for auditions, solos with the orchestra, and recitals?

Similar to my students, I work a lot on the piece to make sure it’s in tune. I also delve into phrasing so I don’t sound mechanical. It’s important that I practice with my accompanist as much as possible, because I don’t do well if we just practice once or twice. Even when I’m playing with an orchestra, I still practice with my pianist and play for nursing homes and other venues before the performance with the orchestra so that I’m really comfortable with the work. This way, even if it’s not my best performance, it’s still a good performance. It takes a lot of work, but it’s worth it.

Do you have any final words of advice for violin teachers?

Being a teacher is a very noble profession. Regarding students’ playing, they definitely need to work on technique. You have to listen to it in the lesson, or else they won’t practice. Scales and arpeggios build the foundation of our playing. Once you have built the foundation, you can do anything.

I believe it is important to have recitals and goals. Without goals, none of us work as hard. It’s more work but it’s worth it.

My students are like a family. We critique each other for our mock auditions, but they are supposed to be kind, too. They learn a lot from collaborating and talking with each other. They’ll say funny things like, “I know I don’t do this very well either,” but they notice when it happens.

Lastly, love your students. Remember that each one is different. We have to be stricter with some to get them to practice, whereas others start crying if you don’t use a more gentle approach. You want to build a rapport where they believe in you, care about you in return, and want to work hard. We influence students in so many ways besides just music. Sometimes they won’t listen to their parents, but they might listen to us. As a result, it’s important we build our relationship with them. I care about my students dearly, like my own children.